For the lone wolves

There was a boy who grew up in a little hamlet of St. Peter's, located in Villnöss valley in South Tirol, northern Italy. With no swimming pools and no football fields in the tiny village, his father, a schoolteacher, often brought him climbing. This boy made his first summit, a peak of 3000 feet in the Geislerspitzen range, when he was five; at thirteen, he had overtaken his father.

His love affair with the mountains sparked, the teen spent more and more time in the crags — he would run for hours up alpine meadows to build stamina, and even more practicing moves on a ruined building in the village — and correspondingly, less and less time with his books. Predictably, when he failed his school exams, he bore the unbridled wrath of his father, an angry patriarch given to violence with his children. As the years pass, the father will repeatedly, vehemently, beat into his stubborn son's head that a career doing what he loved and did best — climbing — was unfeasible, impractical, impossible.

The son never heard him. In his own words, "In the family... there was only one chance. To break, to be broken, or to be stronger than the father." By his 21st birthday, he was soloing the Dolomites.

His family had hopes of him being an architect, and so, grudgingly, this amateur climber enrolled in Padua University. Nevertheless, he continued to spend the majority of his time on the rocks (which explained for his desultory academic progress).

In 1969, he earned his diploma in architecture, but much to his father's chagrin, he opted for a humble (and financially unrewarding) profession of teaching mathematics at a local secondary school, solely because it allowed him to do what he truly wanted — climb. For, it is in the mountains where this young man's true gifts lay. A year ago, some of the world's best climbers at Mont Blanc halted their ascents and peered through binoculars, aghast, as he climbed up Les Droites, then regarded as the most difficult ice wall on earth, in 4 hours. The previous record was 3 days, with the previous three expeditions meeting with disaster and death. That this young climber's speed is preternatural would be demonstrated to the world again and again. In 1974, he scaled the north face of Eiger in 10 hours. On a 1979 expedition to Ama Dablam, he rescued Edmund Hillary's son, Peter Hillary, and two companions. What took the New Zealanders two and a half days to climb, he covered in 6 hours.

Apart from his gift of uncanny speed (another climber, Nena Holguín, gasped, "he moved like lightning across the snow. You know how deer are light-footed—he would seem to spring; it seem like he hardly touch the ground") he also possessed incredible self-sufficiency. And self-reliance:

In an essay he wrote when he was 27, he decried the siege tactics that allowed even an unskilled climber to conquer a mountain bolt by bolt, issuing a plea for both the mountain that cannot "defend itself" and for the climber, who was being cheated of the opportunity to test the limits of his courage and skill. Titled The Murder of the Impossible, the essay, now considered a minor classic, argued that the wielders of expansion bolts and pegs "thoughtlessly killed the ideal of the impossible." His characteristic minimalism — he is adamant he has never put an expansion bolt in a face of rock, as he has never used bottled oxygen — was, therefore, a brash demonstration that the principles he preached could be put to spectacular practice. His landmark high-altitude alpine-style climbs liberated both the individual climber, by showing alternatives to the hugely encumbered and expensive classic expeditions, as well as the mountains themselves.

This tore up the rule book for high altitude mountaineering: gone was the use of supplemental bottled oxygen; gone were the big teams, porters, sherpas, crevasse ladders, fixed ropes, pitons, bolts, and staged camps. This philosophy came to be known as climbing "by fair means." He would leave base camp with a rucksack, climb as fast as possible, and then descend.

And self-confidence: in 1978, he stunned the climbing world by being the first person to solo an eight-thousander alone — Pakistan's 8125-meter Nanga Parbat. Prior to that, he pulled off a historic feat, something that medical experts said couldn't be done: climb to the top of Mount Everest without using supplemental oxygen. Doctors and climbers regarded the human body incapable of surviving above 8600 meters without bottled oxygen. In Germany, at least five doctors on television appeared before, going and telling everyone they can prove climbing the biggest 8000-meter peaks without supplemental oxygen was not possible. On 8 May 1978, he stood on the 8850-meter summit of Mount Everest — without bottled oxygen. Even his father became a believer: sitting in the local bar, upon hearing news of his son's success on Everest, he exclaimed, "I knew he would do it!"

Two years later, he would return to shake the world with an even more astounding feat: he soloed Mount Everest without oxygen, climbing to the summit and returning in a little over 3 days. No rope, no buddy, just a small rucksack. There were no other climbers on the mountain. A climbing legend, Sir Chris Bonington, opined, "That solo ascent is the most remarkable attempt on Everest ever. Add to it what he achieved later and he is undoubtedly one of the greatest mountaineers of all time."

On 16 October 1986, standing on the summit of Lhotse (8501 meters), he became the first man to climb all fourteen 8000-meter (26,240 feet) peaks on the planet — and all by fair means.

Today, he is acknowledged as the undisputed world's greatest mountaineer.

Who is he?

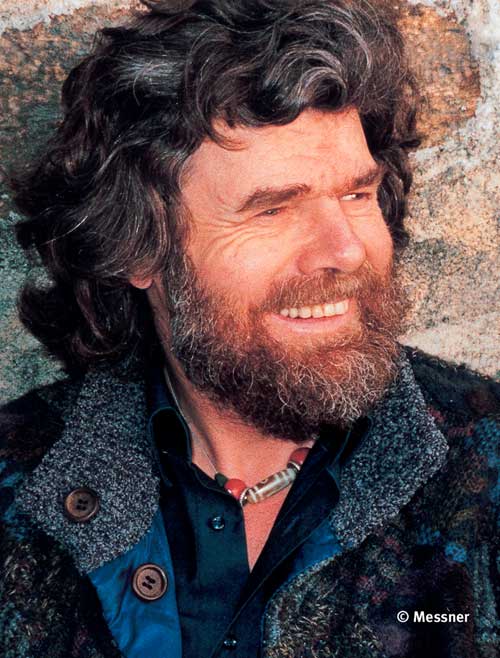

He is Reinhold Messner.

In pursuing his heart, Reinhold Messner changed the world of climbing. He tore up the rule book for high altitude mountaineering — and replaced it with his own:

Messner, 62, is not only the greatest high-altitude mountaineer the world has ever known; he is probably the best it will ever know. His 1980 solo ascent of Mount Everest by "fair means" — without sherpas, crevasse ladders or supplemental oxygen — remains the most primal test conceivable of man against the earth. (James Graff, Time)

What is most admirable (at least to me) is that Messner did all these for one reason and one reason alone — himself. "I am Sisyphus," he has written, " and the stone which I push up the mountain is my own psyche." He did not do it for fame. He did not do it for riches. And, to the rancor to many of his countrymen, neither did he do it for country:

At a local festival held to honor the success of the 1978 Everest expedition, Reinhold was asked why he had not carried his country's flag. "In my answer, I said I didn't go up for Italy, not for South Tirol, not for Austria, not for Germany," Reinhold said, laughing hard enough to sputter. "I went up for myself. I took out my handkerchief: 'I am my own home and my handkerchief is my flag.' Nobody's going up for somebody on Everest. You go by yourself, and you handle it yourself."

At another time, Messner proved more colorful:

"All this nationalistic chanting makes me angry. I cannot stand it. I am not an anarchist, but I am anarchistical. Nature is the only ruler. I shit on flags. I do not need a national feeling. We are not something special. The time of the flag has been over for 50 years. And we know what tragedies nationalism brought to Europe in the last century."

Perhaps there's method in his madness: Nena Holguín, referring to his unprecedented solo ascent of Mount Everest in 1980:

Reinhold had already soloed about 2000 mountains at that point. People don't think of it as easier, but it's easier sometimes to do things alone because there is nobody you have to cooperate with, as long as you can get past the aloneness. He likes to do things exactly at his own pace and his own style. It's easy to do things alone if you already know you can do them. He trusted himself entirely.

But being the lone wolf has its price: Hans Saler, a member of the ill-fated 1970 Nanga Parbat expedition where Reinhold's brother, Günther perished, wrote in an open letter, "Our silence had to do with loyalty, a foreign word for you. You are an excellent climber, but a good comrade? NO!"

As evinced by Saler, even his detractors acknowledge their respect for Messner's achievements, however grudgingly. Douglas Scott, a British high-altitude alpinist has this to say:

Everyone likes to bash the icon, so I would take all this with a pinch of salt. Messner did not climb new routes in the Himalayas. He did what had already been done - with lightweight equipment and without oxygen. But he broke grounds in terms of style and his solo ascents of Nanga Parbat and Everest were great steps forward... He is a real mountain man with mountain intelligence. He has his detractors, but much of it is envy.

In his unbridled pursuit of his passion, Messner blazed a path so bright — so long, so wide — that, perhaps, for many generations, others can only follow. In the words of Jürgen Winkler, a distinguished alpine photographer, "Reinhold Messner is un homme extraordinaire. There is no second person in the world like Reinhold Messner."

"He had nobody's footsteps to follow," says Ed Viesturs, an American climber who completed the fair-means ascent of all 14 [8000-meter] peaks in spring 2005. "After Messner, the mystery of possibility was gone; there remained only the mystery of whether you could do it."

"Messner set the agenda for mountaineering after all the big peaks had been climbed," says Ian Parnell, one of Britain's top alpinists. "He set out the rules that we are still using today."

Acknowledged as the greatest mountaineer in history, Reinhold Messner, also a writer (an author of over 40 books), lecturer, photographer, European parliamentarian, owner of a vineyard and several organic farms, now lives in Schloss Juval, a fully restored 13th-century castle perched on a 3000-foot-high-cliff, guarded by soaring, snow-streaked mountains, overlooking Senales Valley. With his lucrative endorsements, highly paid lectures and book royalties, he is worth millions. Today, the 62-year-old spends his time writing books, making documentary films, contributing to well-known specialist magazines (e.g. Alpinist and Gripped), advocating the preservation of wilderness, mountain farming, and building and running a series of mountain museums. Not bad for a stubborn village lad who chose to follow his heart and refused to "grow up," eh?

If you look at my life, then one thing is clear. I did one activity at a time, with all my willpower, all my money and all my time. Complete commitment.(Reinhold Messner at Castle Juval, his home in South Tirol, Italy)

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home